The canal to Edinburgh was one of the last to be built in Britain and was built much later than the Forth and Clyde canal and Monkland canal which were respectively opened in 1790 and 1794. It took 25 years to decide the route of a canal from Edinburgh to Glasgow. During this time seven different routes were considered before the route of the Union Canal was confirmed in 1818.

1793 – First Edinburgh Canal Proposals

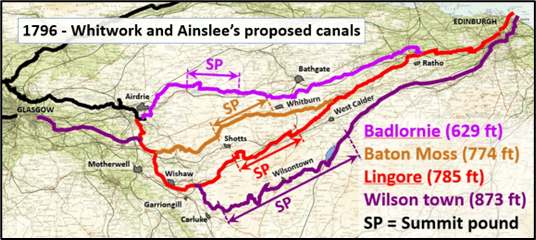

A committee of subscribers was formed in 1793 to engaged Robert Whitworth, previously chief engineer of the Forth and Clyde Canal, and John Ainslie, a surveyor on the Forth and Clyde canal, to survey possible routes between Edinburgh and the Clyde valley’s coal mines which were the nearest known significant coal deposits to Edinburgh. They developed four options from Leith with summit pounds between 629 feet and 875 feet above sea level. The highest route would have had about a hundred locks and been 230 feet higher than the UK’s highest canal, the Huddersfield canal.

Proposals to build canals over such high ground show the importance of the Clyde valley’s coal as well as local industries on these routes. At Williamstown for example there was an iron works with two blast furnaces.

1797 – Northern option added

In 1797, famed Civil Engineer, John Rennie, reviewed Whitworth and Ainslee’s proposals. He discounted the two higher routes, improved the other two and suggested a new route of his own. This was to be a contour canal on a Northern route. This was to follow a similar route to the Union Canal that was eventually to be built but be 24 foot above it. Instead of connecting to the Forth and Clyde, it would follow a route past Cumbernauld to join the Monklands Canal near Coatbridge.

However, nothing was to come of any of these proposals due to the Napoleonic wars which started in 1803. Due to its dire economic consequences, there was no money to build canals.

1813 – Interest revived

By 1813 the Napoleonic war was coming to an and significant coal deposits had been discovered around Falkirk. This, together with an increasing demand for coal from Edinburgh’s increasing population, revived interest in a canal. Hence, a group of subscribers asked Hugh Baird, resident engineer to the Forth and Clyde Canal, to survey a route from Edinburgh to Falkirk to connect with the Forth and Clyde canal. His proposal became the Union Canal which Thomas Telford considered to be “the most perfect inland navigation between Edinburgh and Glasgow.”

However Baird’s proposal was contentious as it did extend the canal to Leith although an 1817 map of Edinburgh does show “the line of a canal proposed by Mr Baird” from Port Hopetoun to Leith docks.” Instead, it terminated at Port Hopetoun on Edinburgh’s Lothian Road, although an 1815 plan also shows a canal basin on what it today ‘The Meadows.’

1814 – A level Edinburgh to Glasgow canal

In 1814 Robert Stevenson, of lighthouse fame, proposed what he considered to be a better alternative which included Leith and was instructed by the City Council to produce a report on his route.

His survey confirmed that Port Dundas in Glasgow, on the summit pound of the Forth and Clyde canal, is 35 feet below the level of Princess Street which is the same level as the current railway through Princess Street Gardens. He then surveyed a contour canal from a proposed basin under the North Bridge to join the Forth and Clyde canal just west of lock 20 near Castlecary. This is the eastern end of the canal’s summit pound which is 155 feet above sea level, 85 feet below Hugh Baird’s proposed canal. However, his route required a 3-mile-long two-way canal near Winchburgh which was estimated to account for £132,000 of the £404,000 cost of his 31.5-mile-long canal.

His report stressed the cost of the tunnel would be worth it for the large amount of freight and passenger traffic that a level canal would attract. It advised “no ideas of fear or apprehension are connected with canal tunnelling” which is by no means uncommon in England. However it did acknowledge that some passengers might object to passing through the tunnel and suggested that, for such passenger, that a coach could be provided to travel these three miles by road.

1817 – Decision time

Once Stevenson report was published it was time for a decision. Rennie’s 1797 proposal had already been ruled out after coal finds in Stirlingshire. Despite the arguments in Stevenson’s report, subscribers were unwilling to bear the cost and risk of the 3-mile Winchburgh tunnel and chose Hugh Baird’s significantly cheaper route which was estimated to cost £241,000. The route to Leith was considered to be too expensive and problematic, in part due to its 16 locks.

In March 1817, just one month after Stevenson presented his report, the Union Canal bill had its first reading in Parliament. It received Royal assent in June which allowed construction to start in 1818. The canal opened in 1822. As this was only 20 years before the Edinburgh to Glasgow railway opened, it was to have a short commercial life.